BROCHURE

Contact YPT for a detailed information about YPT Agglomeration Drums.

YPT Quality Management System

For detailed information about YPT Quality Management System

YPT Process Equipment Factory

For detailed information about YPT Process Equipment Factory

Uniform Agglomerates — Consistent Leaching

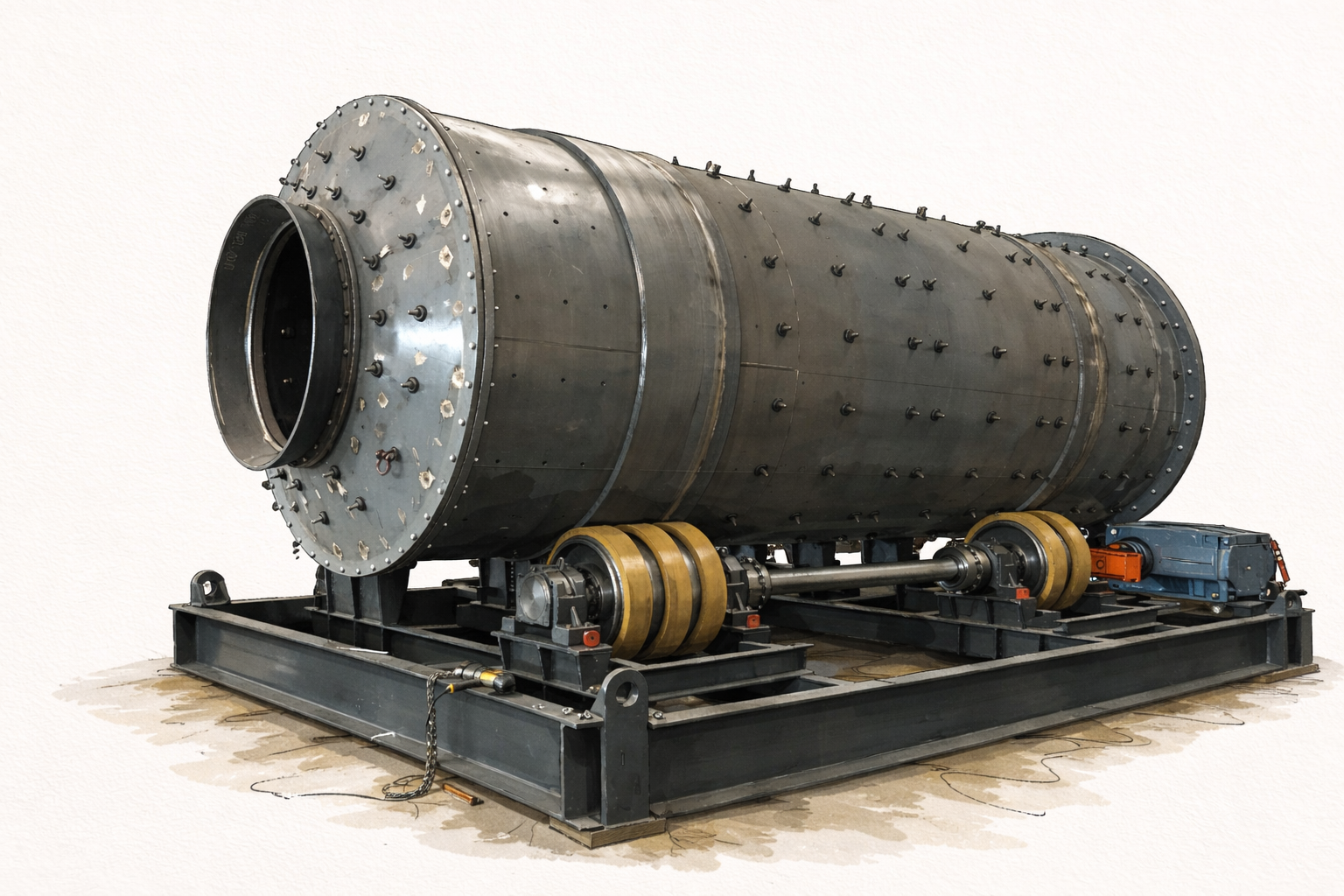

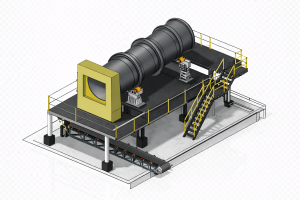

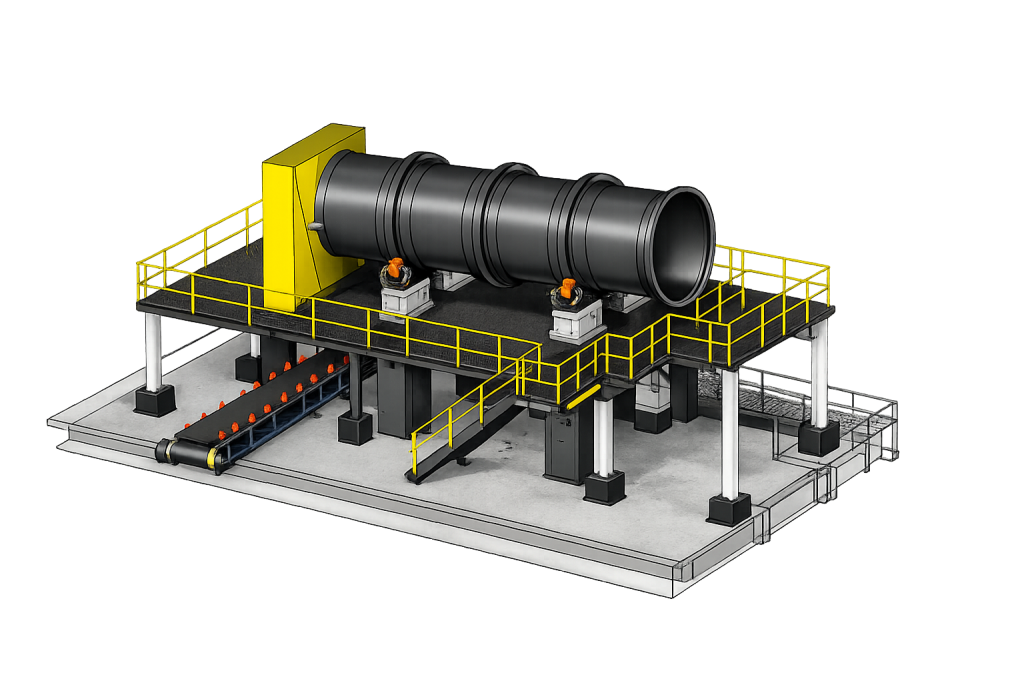

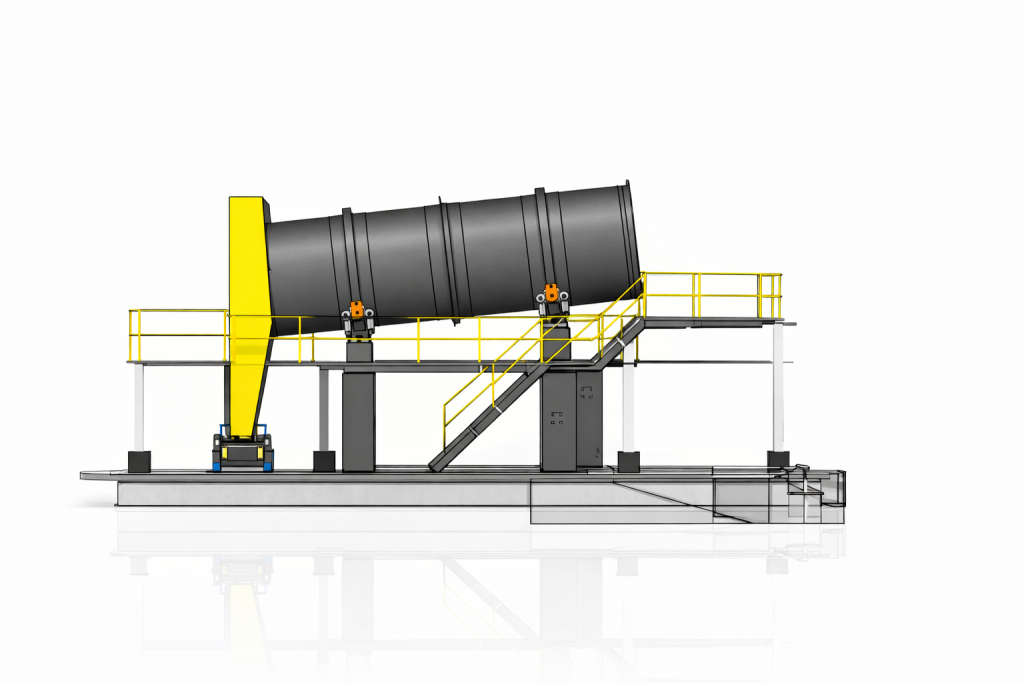

YPT Agglomeration Drums

An agglomeration drum is a large, rotating cylindrical vessel, typically mounted on a slight incline, in which crushed ore — especially fines-rich or clay-bearing material — is tumbled together with a liquid (water or leach solution) and a binder (such as cement, lime or polymer) so that the fine particles adhere and grow into larger, more robust aggregates (agglomerates).

These agglomerates are then discharged and stacked onto a heap-leach pad or otherwise processed.

The purpose is to transform a problematic fines-rich material into more permeable, uniformly sized, stable granules that will perform better in downstream processes.

In the context of heap leaching, the agglomeration drum operates as an ore-conditioning unit between crushing/screening and stacking.

By converting loosely packed fines into stronger, coarser granules, it improves solution flow, reduces channeling or ponding, and enhances recovery efficiency.

These agglomerates are then discharged and stacked onto a heap-leach pad or otherwise processed.

The purpose is to transform a problematic fines-rich material into more permeable, uniformly sized, stable granules that will perform better in downstream processes.

In the context of heap leaching, the agglomeration drum operates as an ore-conditioning unit between crushing/screening and stacking.

By converting loosely packed fines into stronger, coarser granules, it improves solution flow, reduces channeling or ponding, and enhances recovery efficiency.

Areas of Application

The key application area of agglomeration drums is in heap leach operations of precious and base metals — for example gold, silver, copper, uranium — especially when the feed material has a high fines content or contains clay minerals that hamper permeability.

When the amount of material finer than –74 µm (200 #) exceeds about 5 % of the feed, then agglomeration is often necessary and when the fines fraction exceeds 10-15 % a binder will almost certainly be required.

Beyond mining, the principle of agglomeration drums is also used in other industries (chemicals, fertilizers, waste‐processing) to convert powders or fines into flowable, handled granules, but in mineral processing the focus is on ore conditioning for heap leach or pre-stacking.

Principle of Operation

The process inside an agglomeration drum can be described step-by-step as follows:

From a design viewpoint, key physical principles include the interaction of tumbling motion (drum speed, diameter, lift flights), residence time (controlled by inclination and speed), binder and liquid dosage (to achieve sufficient strength and porosity), and discharge size/strength. Studies show that agglomerated heaps often achieve significantly higher recoveries versus non-agglomerated ones under comparable conditions (especially for fines/clay rich feeds)

Stronger Pellets. Better Percolation

YPT Apron Feeder Highlights

Where Fine Particles Become Process-Ready

Design Criteria

When designing or specifying an agglomeration drum, several important design criteria must be addressed:

Throughput / | The drum must match the tonnage rate of the mine or the feed rate to the heap. Some drums are rated up to 3 000 + t/h in large heap-leach installations. |

Shell geometry | Larger diameter and longer length increase residence time and capacity. Typical diameter ranges for industrial units span ~1.0 m to ~4.6 m (or more) with lengths up to ~10 m+ depending on scale. |

Inclination angle: | The drum is mounted with a slight slope (often ~3°-5°) from feed to discharge to allow gravity to assist movement and control residence time. |

Rotation speed: | The RPM (or peripheral speed) influences the tumbling action and residence time. Too fast may reduce time for agglomeration; too slow may reduce throughput. One review suggests typical speeds in the order of ~7-16 rpm for certain diameters. |

Internal lifters/flights: | The drum interior often includes flights or lifters that lift the material as the drum rotates, then drop it, promoting mixing and tumbling. The geometry (flight height, spacing) affects residence, mixing, wear and aggregate formation. |

Binder and liquid | The spray system must provide uniform wetting of the ore bed, maintain the correct moisture content and binder dose (e.g., cement, lime, polymer). The binder dose depends on ore fines content, clay mineralogy, target granule strength and leach conditions. For example, in copper heaps, acid + water additions might be ~15-25 kg H₂SO₄/t ore and ~60-100 kg water/t ore |

Materials of | Because ore is abrasive and the internal environment is aggressive (wet, spray, binder, fines), the shell, liners, flights and seals must be designed for wear. Rubber liners, AR steel, or composite liners may be used. For example, tyre-drive drums may use rubber tyres to support the shell and allow for robust service |

Discharge and | A discharge end trommel or screen may be used to segregate undersized or oversize material; undersize may be recycled to enhance size control and quality of the agglomerated product. |

Instrumentation & | Monitoring feed rate, drum speed, binder flow, moisture content, aggregate size/strength, drive power draw and vibration is important for optimal performance and maintenance. |

Technical Specifications

Below are representative values for an industrial agglomeration drum. These values should be adapted to the specific site, ore characteristics and test-work results.

Drum diameter: | ~1,000 mm to ~4,600 mm (1.0–4.6 m) | Larger diameter for higher throughput |

Drum length: | ~5,000 mm to ~10,000 mm+ | Length scaled for residence time |

Inclination angle: | ~3° to ~5° | Controls residence time via gravity flow |

Rotation speed (RPM): | ~7 to ~16 rpm | Depends on diameter and material |

Throughput (tonnes/h): | Up to ~3,000 t/h+ in large units | Dependent on feed size, binder dosage |

Feed size: | Typically crushed ore (< 25 mm) or as per feed specification | High fines content dictates need for agglomeration |

Binder dosage: | Varies widely (e.g., cement / lime / polymer) | From pilot test‐work |

Materials of construction: | Shell: steel; Liners: rubber or AR steel | Designed for abrasion and corrosion |

Note:

These numbers are indicative only. It is essential to conduct ore test-work (agglomerate size/strength, fines content, binder optimisation) to determine actual design values.Important Considerations:

Installation and Operation

The foundation must support the large mass of the drum, rotating shell, drive system, tyres/trunnions, service access and alignment systems. Alignment of tyres/trunnion wheels and shell is critical to prevent shell stress and excessive wear. The spray system, binder storage/pumping system and feed/discharge conveyors must be properly installed and commissioned.

During operation, the feed rate, binder dosage, spray water, drum speed and inclination must be monitored and maintained within design ranges. Change in feed fines content or clay content may require adjustment of binder dosage or drum operating parameters. It is often advisable to monitor the strength of the agglomerate (for instance by crush testing) and the size distribution on discharge to ensure consistent performance.